The applications are obvious in the educational domain. Mostly I’ve focused on the effects on learning. Wouldn’t this technique backfire with optional reading-say, in a magazine? Your research focuses on assigned reading material, often in a classroom setting. The same could be said of small font sizes. That isn’t something people can adjust to the weaker contrast is simply harder to see. A gray font on a white background is harder to read than black on white.

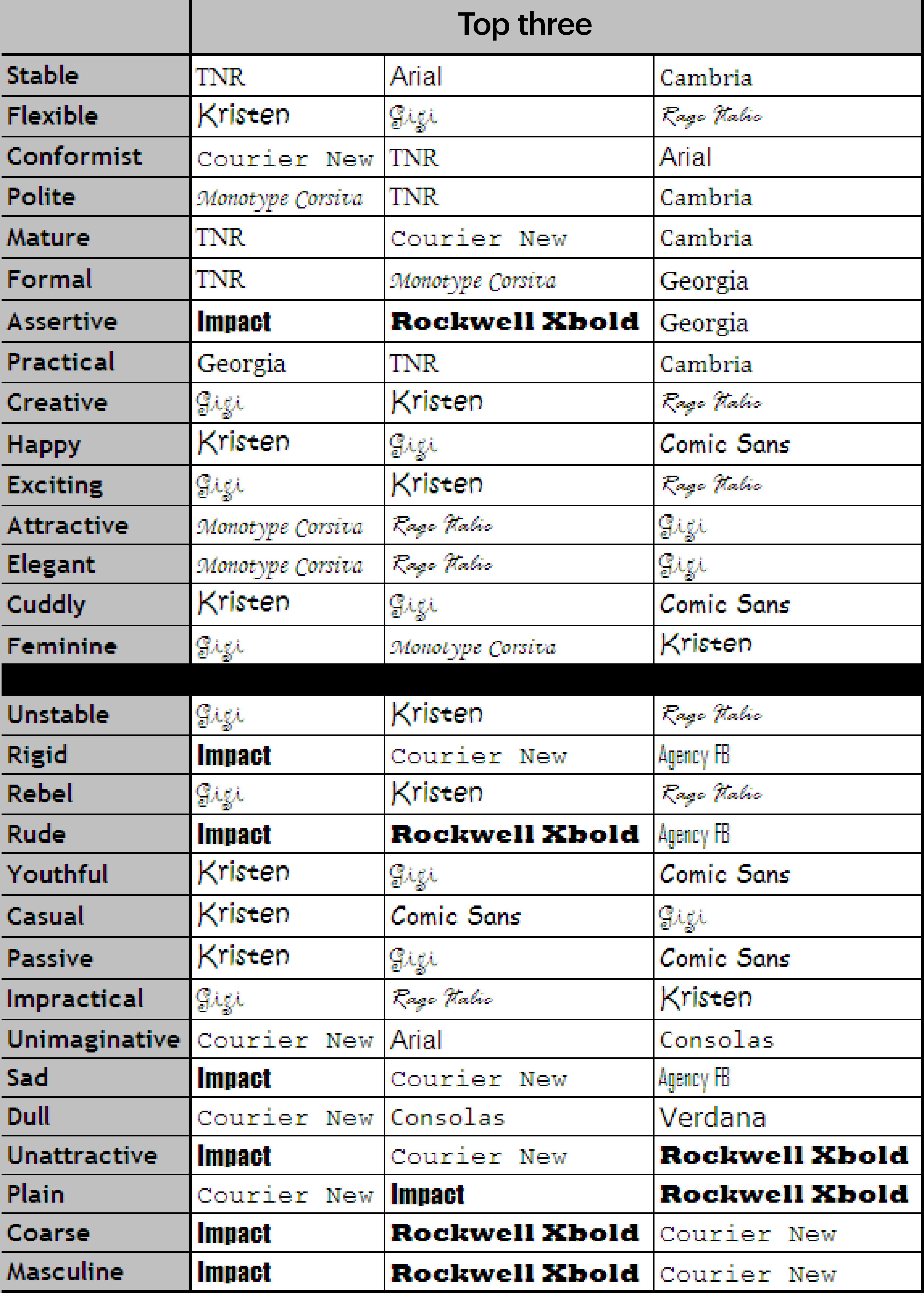

Another way to create disfluency is to manipulate contrast. In a textbook you could get around that by using a different font in every chapter. One of them is by using a font that people haven’t seen before, and indeed, with enough practice people will adapt to it and become fluent. You can manipulate disfluency in a number of ways. Wouldn’t people adapt to a new font over time, weakening the effect? But when people look at Monotype Corsiva versus a “normal” font like Arial Black, there’s 100% agreement that Monotype Corsiva is harder to read, and we see really high recall with it. I’m not an expert in typography, and we’ve never looked at what the optimal fonts are to create disfluency. If we want people to really remember this interview, what font should we use? If readers encounter a disfluency-something hard to decipher-they become less confident in their ability to understand, and that nervousness makes them concentrate harder and process the material more deeply. There’s a lot of evidence that difficulty in processing is strongly related to confidence. HBR: So the difficult fonts act like speed bumps? Of course, we don’t want to make material so hard to read that people can’t understand it. So it’s not terribly surprising that causing people to slow down and read more carefully improves their recall.

Making text harder to skim prevents that from happening. For instance, we’ve all skimmed through text, got to the end, and realized we didn’t process the information very well. Why should making something harder to read make it easier to remember? But the findings are more intuitive if you reframe them.

Oppenheimer: When people first hear about this work, they’re surprised. When students were shown two paragraphs in different fonts, they remembered 14% more of the facts printed in the hard-to-read font.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)